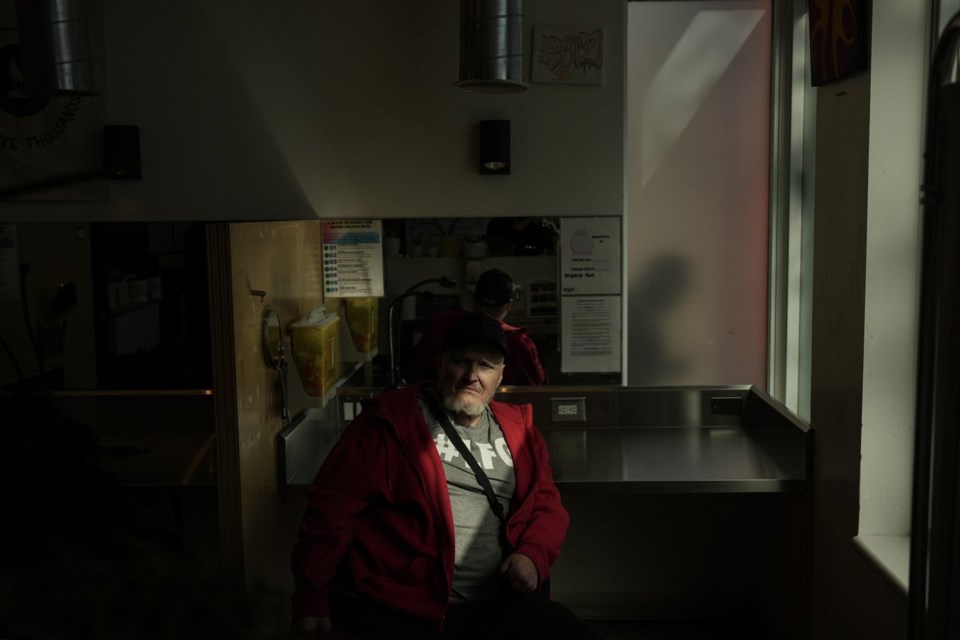

TORONTO — Mike Erickson wheels his power chair around a Toronto supervised consumption site, waiting for his friend to show up.

He has tested his fentanyl there and the results showed it did not have any of the "garbage" – animal tranquillizer or benzodiazepines – that is increasingly mixed with the deadly opioid sold in the city.

He skipped testing his drugs one day about a month ago and some of that garbage nearly killed him.

He remembers injecting what he thought was pure fentanyl into a vein and immediately going under. He recalls snippets of consciousness from that time: screaming at the staff who helped him breathe for 15 minutes and administered naloxone, the opioid antidote.

"I thought I was already dead and in hell," Erickson says. "I couldn't remember where I lived, couldn't remember my girl, couldn't remember nothing."

Yet, he was alive.

Erickson is a regular at two sites run by the Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre. He's addicted to fentanyl and has lived a difficult life. He lost his legs and fingers to diabetes complications years ago and gets around in a motorized wheelchair.

The Canadian Press visited the Queen Street supervised consumption site on a recent Friday before it shuttered its doors on April 1. That's the day a new Ontario law came into effect banning such sites located within 200 metres of a school or daycare.

The centre is participating in the legal case of another Toronto supervised consumption site that took the province to court, challenging the constitutionality of the law.

A judge heard the case in late March and granted an injunction to allow 10 such sites to remain open while he considers his decision. But nine of the 10 sites had already agreed to transition to the province's new abstinence-based model – homelessness and addiction recovery treatment hubs, or HART hubs – and closed.

The province will give the new sites about four times the money it gave supervised consumption sites. But Health Minister Sylvia Jones's office recently told The Canadian Press the provincial funding was contingent on the new hubs discontinuing use of supervised consumption services.

Jones has said the government is shutting down the sites due to safety and security concerns, especially for children.

The Queen Street site is among those that chose to transition to one of the new hubs.

Josh McLean, who lives in a shelter near Lake Ontario, has been coming to the site over the past year. The 40-year-old has been homeless since the age of 16 and is now addicted to crystal meth. Like many others, McLean has overdosed a few times and was brought back to life at a supervised consumption site.

"I mostly feel safe here," he says. "People don't judge you, they teach you how to care about life again."

Another site user, Brendan Fitzpatrick, had just moved to Toronto the day before. He says he lost a family member in Kingston, Ont., and had nothing left to keep him there. But before he left that city, he was able to get off fentanyl with help from a local consumption site, the Integrated Care Hub.

Now he's on methadone and no longer craves the opioid, but will sporadically get high on crystal meth. For that, he goes to a supervised consumption site.

But the journey off fentanyl took a long time, he said.

"The hub and the community in Kingston really helped me," he said. "They set me up with a methadone doctor and it honestly changed my life. The thing is, if it wasn't for a safe injection site, I don't think I'd be clean of fentanyl today, you can't just do it on your own."

The waning days of the site weighed on staff, too.

Patrick Murray becomes emotional when contemplating his time as an overdose prevention support worker. The situation is overwhelming if he thinks about it too much.

"It's hard when you're on a team you believe in, you believe in your job and you actually help save people from dying," he says. "And our clients seem to appreciate our work. So now it feels like I'm in the band on the Titanic, playing music and everyone's scared and sad."

But outside the Queen Street site, where garbage and several needles were strewn in a nearby alley, finding acceptance among neighbours has been a challenge.

Lois Dellert's home backs onto that alley. She has lived there since 2008 and supports supervised consumption sites in general. She got to know a few site regulars because they hung out in the alley and says break-ins, vandalism and violence were rare.

"I didn't feel afraid," Dellert says.

But she says the situation changed in 2023. Since then she's seen a lot: drug use, drug deals, fights, discarded needles, theft and vandalism of homes and garages, and people passing out.

She has been woken up at all hours of the night, threatened numerous times and feels like an outsider in her own neighbourhood.

Dellert says she's tried numerous times to discuss the situation with the site, but there wasn't much engagement. Site managers often said they could not control what happened outside its walls, she says.

"I'm hopeful the new rules will return our neighbourhood to what it was like just a few years ago," Dellert says.

"But I'm also sad. It is not the safe consumption site itself that was the issue, it was the way it was being run in the last two years. And when we brought up specific complaints, we were discounted and excluded and it felt like the work they're doing outweighs any negative impact to the neighbourhood."

Dellert has no idea what to expect now that the site has stopped offering supervised consumption services.

So far little has changed in the neighbourhood from her vantage point, though it's only been a few days since the closure.

But it's a monumental change for those with little else, Erickson says.

"We're going to get bodies in alleys, we're going to get bodies in parks."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 11, 2025.

Liam Casey, The Canadian Press